Alex Chilton, who died last week at the age of 59, had a strange and complicated relationship with fame. He achieved it early as the lead singer for the Box Tops, struggled to recapture it in the 1970s with Big Star, and spent a decade pushing it away after that band broke up. As easy as it is to imagine an alternate reality in which Paul Westerberg's line above is more than just a fantasy, that's not what happened.

Chilton was just 16 when "The Letter" topped the U.S. singles chart in 1967. The song isn't even two minutes long, but it set the course for the rest of his life. After its success, his parents let him quit high school, where he was already failing, to be in the Box Tops full time and try to succeed as a musician. The band scored several further hits and became one of the defining blue-eyed soul groups, due in no small part to Chilton's gritty-beyond-his years vocals.

In spite of their success, Chilton grew unhappy with the Box Tops and precipitated the band's breakup by storming offstage in mid-performance in late 1969. After turning down an offer to become the lead singer for Blood, Sweat & Tears-- he thought the band was too commercial-- Chilton worked to become a better guitarist and began an abortive attempt to record a solo album (the results can be heard on Ardent's 1996 compilation 1970). Ultimately, he found himself back home in Memphis, where he joined Big Star in 1971.

In Big Star, Chilton dropped the soul-man vocal style he'd made his name on in favor of a reedier, more natural delivery. He found a natural partner in the band's other main songwriter, Chris Bell, and the quartet cultivated a sound indebted more to the guitar-driven Byrds and the British Invasion bands than to their hometown's soul heritage. Their first album, optimistically (or sarcastically, depending on who you ask) titled #1 Record, is a deathless power-pop masterpiece that garnered considerable acclaim on its release in 1972 and deserved every bit of it.

Listening to the album today, it's striking how much variety and tension the band packed into it. "Thirteen" is haunted and desperate, "When My Baby's Beside Me" is celebratory and propulsive, "Don't Lie To Me" explodes with macho energy, while the gentle, acoustic "Watch the Sunrise" matches its intensity in spite of its beauty. "In the Street" is the only Big Star song a lot of people know on account of its use (in a cover version by Cheap Trick) as the theme song for "That 70s Show", and you can see why the show's producers chose it: Is there a couplet that embodies suburban teenage boredom more completely than "Wish we had/ A joint so bad"?

#1 Record could have launched Big Star into orbit, but the record industry got in the way. Stax Records was in decline and unable to adequately distribute the album-- when kids who'd read the rave review in Rolling Stone went out to buy it, it was nowhere to be found. It only got worse when Stax signed its distribution over to Columbia, which had no interest in Big Star and pulled the few copies of the album that had made it to shelves. The album's failure nearly destroyed Big Star. Bell, who'd already seen Chilton eclipse him in his own band, quit the group, then rejoined. They broke up after a few months of tumult, and finally reconvened without Bell.

Radio City, the resulting album, is nearly as good as its predecessor, and bristles with a charged, live feel. On its own, #1 Record probably would have been enough to build a legend for the band, but the two albums together, as they've often been sold in subsequent reissues, are extraordinarily powerful and influential. They work as a pair to paint an amazing picture of American youth and all its contradictions, frustrations, desires, and disappointments.

Radio City's fate is a near mirror-image of #1 Record's. Columbia barely distributed it, and all the great reviews in the world weren't enough to make a hit out of a record no one could obtain. Bassist Andy Hummel left to focus on school, leaving Chilton and drummer Jody Stephens to carry on as a pair, working with producer Jim Dickinson on the third Big Star LP.

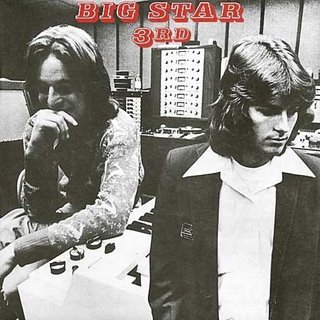

Sister Lovers, which Columbia refused to even release at the time, is a fractured, defiant document of a band that seemed to have stopped caring whether their music topped the charts or played on the radio. Chilton had always tried to do things his way, but here, he took that to an extreme, creating a record stretched bizarrely between the poles of refined orchestral pop and crumbling, willfully difficult soundtracks for clinical depression.

The string arrangements on the album are never anything short of stately, which makes them sound all the more odd sawing their way out of tangled songs like "Stroke It, Noel" and "Nightime", the latter of which is the most ghostly song in Chilton's varied discography. When the album was rejected, Big Star called it quits, and Chilton headed out on his own in late 1975, restarting the solo career he'd put on hold for Big Star.

From the sound of his first eight years of solo work, Chilton had no interest in trying to play ball with record labels and radio programmers. He produced early records by the Cramps and left Memphis for New York. His solo work in the late 70s and early 80s was confrontational and often had more in common with the Red Krayola than the Beatles and the Kinks. His 1979 solo album, Like Flies on Sherbert, is one of the most ramshackle, messy LPs I've ever heard, and that's obviously the intent. It's as though, finding himself thwarted when he tried to achieve success and fame on his own terms, Chilton reversed course and tried as hard as possible to push the spotlight away from himself.

And it would have worked, too, if it hadn't been for the fact that the Big Star albums were too good to stay hidden forever. Young musicians discovered them and sang their praises. Suffice to say American college radio would have sounded awfully different in the 80s if not for Big Star. It's hard to even imagine R.E.M. without them, and of course the Replacements made their debt to Chilton clear on Pleased to Meet Me. Chilton himself didn't quite get all the fuss over the Big Star albums. In a 2007 interview with Russell Hall of Gibson Guitars, he put it this way: "I'm not as crazy about them as a lot of Big Star cultists seem to be. I think they're good, but then again, I think Slade records are good, too."

Chilton's solo work in the mid 80s backed away from the intentional disarray of his early material, gravitating toward R&B and blues, and he was quietly prolific during the 90s. He and Stephens got back together with the Posies' Jon Auer and Ken Stringfellow standing in for Hummel and Bell in 1993, and over the past decade, that quartet continued to tour and even recorded an album together. Chilton had something of a dual reunion life, playing to hip indie rock kids in Big Star while also doing the occasional oldies circuit gig with a reunited Box Tops.

In his later years, Chilton settled in New Orleans. He'd been planning to play at SXSW this past weekend, and seemed comfortable with his elder-statesman status. He managed to finally achieve some of the success on his own terms that had so long eluded him-- the world sometimes takes a while to catch up to a great artist.

Essential Listening

#1 Record/Radio City

Sister Lovers

Essential Reading

Big Star: The Short Life, Painful Death, and Unexpected Resurrection of the Kings of Power Pop

Links

Allmusic: Big Star

Big Star wiki

A Tribute To Big Star

Alex Chilton, Big Star, The Box Tops

Big Star Discussion Forum

No comments:

Post a Comment